Research ArticleOpen Access, Volume 2 Issue 3

The Influence of Covid-19 on the Management of Dental Clinics

María Sofía Rey-Martínez1*; José María Martínez González2 ; María Helena Rey-Martínez3 ; José María Suárez-Quintanilla1

1Department of Surgery and Medical-Surgical Specialties, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15705 A Coruña, Spain.

2Department of Dental Clinical Specialties, Faculty of Dentistry, Complutense University of Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain.

3Department of Otolaryngology, Central Hospital of the Red Cross of Madrid, 28003 Madrid, Spain.

*Corresponding author: María Sofía Rey-Martínez

Department of Surgery and Medical-Surgical Specialties, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, University of Santiago de Compostela, 15705 A Coruña, Spain.

Email: mariasofiarey8@gmail.com

Received : Apr 12, 2024 Accepted : May 13, 2024 Published : May 20, 2024

Epidemiology & Public Health - www.jpublichealth.org

Copyright: Rey-Martínez MS © All rights are reserved

Citation: Rey-Martínez MS, González JMM, Rey-Martínez MH, Suárez-Quintanilla JM. The Influence of Covid-19 on the Management of Dental Clinics. Epidemiol Public Health. 2024; 2(3): 1051.

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to describe the consequences of COVID-19 on the management of dental clinics by dentists in Galicia. A study was carried out with 347 professionals in which aspects related to their personal and social data, their professional activity and their emotional state were evaluated.

83% said that patients’ demands, expectations and moods had changed and 50% of the professionals responded that they felt more sensitive to patients’ criticisms of their treatments and to a greater extent the dentists who have less decision-making power (p=0.005) and management of their clinics. 87.90% of the dental professionals reported a decrease in income between 10,000 euros and 60,000 euros. Nearly 74% of the professionals reported a decrease in patients of between 10% and 25%. The feeling of loneliness is common among dentists and 50% would like to make profound changes in human resources management and in the use of protocols.

56% of respondents indicated the need to make a radical change in their life, with separated or divorced dentists being the group that most often considered this circumstance (p=0.003).

Finally, the emotional and financial consequences had a significant impact on the lives of these professionals. The results of this study will help to better manage future pandemics and provide information for policy makers.

Keywords: Self-employed; Management; Anxiety; Economic activity; COVID-19; Dentistry.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly altered social and working conditions due to the far-reaching changes brought about by SARS-CoV-2 as a result of the policies of social distancing, forced closures, periods of isolation and anxiety about becoming ill, together with the decrease in productive activity, loss of income and fear of the future and all the changes in workplaces and the way work activities are carried out. All these aspects have influenced the mental health of health professionals and their ability to cope with this type of situation [1-4].

It has been widely demonstrated that the work environment, work organisation and work-related behaviours are factors capable of influencing the mental health and psychological wellbeing of workers. Therefore, there is sufficient evidence to consider work-related stress as a factor capable of contributing to cognitive impairment [5].

Dentists have been considered high-risk professionals for aerosol infection, as much of their work involves the generation of aerosols. In order to ensure the safety of both patients and professionals, strict recommendations and protocols were established in dental clinics during the first months of the pandemic.

The compulsory reduction of dental care to emergency treatment was accompanied by severe economic consequences, while at the same time the costs of maintaining the dental practice, such as staff salaries or rent, remained largely constant. During this period, around 30% of Spanish dental practices applied for temporary lay-offs and an unquantified number of dentists lost their jobs. In addition, the prices of medical supplies, such as protective masks (FFP2) or disinfectants, increased exponentially due to higher demand, and as a result the economic pressure on dental clinics increased.

Therefore, dentists have had to overcome many challenges, and the COVID-19 pandemic influenced their physical and mental health, impacted on their family relationships and financial status, with the added pressure of radically modifying their professional protocols. In Poland, the shortage of personal protective equipment created a general feeling of fear, insecurity, lack of preparedness and subjective perception of the risk of COVID-19 infection [6]. In Switzerland, dentists reduced practice activity to a minimum of 0-10% [7]. In Germany almost two thirds of dentists reported a workload reduction of more than 50% compared to the pre-pandemic period [8]. All this has led many professionals to make a personal rethink and a change of attitude towards a profession that was considered by society as a whole to be successful, emerging, lucrative, necessary and respected, and whose foundations have been shaken by the insignificant but powerful force of a virus. This study was planned with the aim of measuring and analysing the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental practices in Galicia, in north-west Spain.

Materials and methods

Study design

This paper analyses a specific selection of information from a larger piece of research that examines multiple aspects of the emotional and economic impact of the COVID-19 crisis on dental professionals in Galicia.

A descriptive observational study was designed for the months of March to July 2021, using the Forms application questionnaire (Alphabet, Mountain View, CA, USA), submitted electronically, which was previously approved by the Ethics and Research Commission of the College of Dentists and Stomatologists of A Coruña (22/1/2021).

Participation was requested anonymously and voluntarily from the professional dental associations of A Coruña, Lugo and Pontevedra - Ourense to all professionals in Galicia (Spain), who at that time were members of these institutions.

Questionnaire design

In developing the questionnaire, several questionnaires widely used in studies of health, job satisfaction and professional quality of life were reviewed (Personal Accomplishment Questionnaire, Maslach Buernout Inventory-MBI-HSS, Copenhagen Burnout Questionnaire, CBI and also the Professional Quality of Life Scale version 5, ProQOL-5) [12-14].

A prior evaluation of the test was carried out with the aim of assessing its reliability, validity, sensitivity and specificity, in a test carried out on 25 professionals in Galicia, who took the test, answering all its questions, in February 2021. As for the results of this evaluation, it was established that the average response time was 11 minutes and 30 seconds. In terms of reproducibility, we obtained a 95.1% agreement rate and a Kappa of 0.879 (95% CI between 0.856 and 0.902). To assess the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s Alpha statistic was used to quantify the level of reliability of a measurement scale for the unobservable magnitude constructed from the n variables observed. The alpha value was 0.84730613578847.

Sample size

Out of a total of 2,208 dental professionals registered in Galicia, 1,243 women and 965 men were asked to participate in the survey. The inclusion criteria were established as being dentists or specialists in Stomatology, working in their own practice. Those professionals working as employees or in the public health system (SERGAS) and those who did not complete the questionnaire were excluded from the study.

In order to calculate the sample size and obtain a representative sample, it was estimated that a minimum of 327 participants was necessary for a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of 5%.

Following responses from 462 professionals, 107 employed or contracted dentists and 8 dentists were excluded because they worked in a public centre, leaving a final sample size of 347 self-employed dentists.

Variable analysis: These were structured in the following sections:

Personal socio-demographic data: age, gender, household members, marital status, sick leave.

Data on professional practice: years of professional work, specialties, number of clinics, number of dental teams, number of employees, workforce reduction in the pandemic, weekly working hours and type of working day, number of patients seen weekly, percentage decrease in patients and decrease in income.

Data on management and COVID-19: consisting of 16 items that were answered as a Lickert scale with 4 options, with values of: 0: Never / not at all; 1: Sometimes / once a month or less; 2: Quite often / once a week; 3: Always / every day.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed with the R program version 4.1.2 and the data obtained were reflected as response frequencies and percentages and 95% confidence intervals. For the analysis of the emotional state, two groups were created according to the Likert scale of the questionnaire item scores (Scores 1 & 2 = not affected, scores 3 & 4 = affected), continuous data were expressed as medians with interquartile ranges, percentages and 95% confidence intervals. Unadjusted logistic regression was performed, where a value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Analysis of the sociodemographic data

In the data set analysed, the average age of the subjects was 48±10.30 years, with ages ranging from 26 to 82 years. The group studied was composed of 60.81% women and 39.19% men.

Regarding marital status, 72.62% of the participants indicated that they were married or in a stable partnership, with families comprising 2-4 members. Despite the health crisis that impacted the general population, only 8% of respondents reported having been absent from work due to illness in the six months prior to the survey, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Sociodemographic data.

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean S/D) | 48/10.3 |

| Sex | |

| Male Female |

136(39.19%) 211(60.81%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married and/or in a stable relationship Separated and/or divorced Single Widowed Other |

252(73%) 43(12%) 45(13%) 4(1%) 3(1%) |

| Number of family members | |

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 |

39(11%) 86(25%) 75(22%) 104(30%) 40(12%) 3(1%) |

| Sick leave in last six months. | |

| yes No |

28(8%) 319(92%) |

Analysis of professional practice

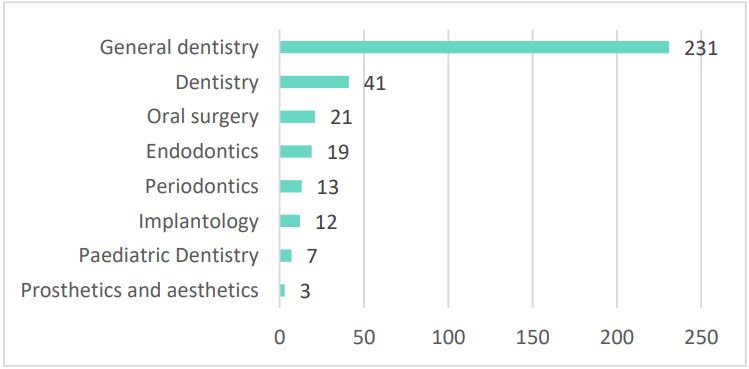

The average work experience of the respondents at the time of participation in the study was 20 years. The majority, 66.57%, were engaged in the general practice of dentistry. 33.43% specialised in specific fields of the discipline, including areas such as orthodontics, surgery, endodontics, periodontics, oral implantology, among others, as illustrated in Figure 1.

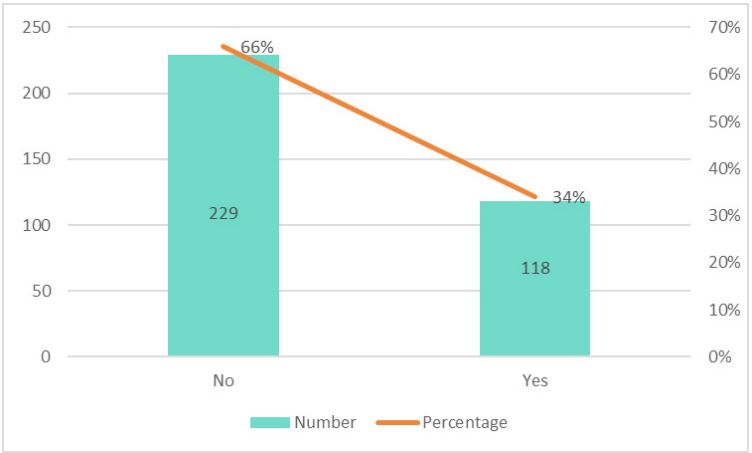

90.77% worked between one and three clinics; one clinic (52.16%), two clinics (26.51%), and three clinics (12.1%). In 96.83%, the number of dental teams ranged from 1 to 5 teams. The number of clinical collaborators prior to the pandemic was mostly between 2 and 5 (61.09%) and during the pandemic, 34.1% of the respondents reported having reduced this number of staff (Figure 2).

The working day before the pandemic was much longer than the conventional one, so that more than half of the professionals (55.62%) worked between 40 and 50 hours, with only 26.51% working a continuous working day, while 66.86% of the professionals worked two shifts.

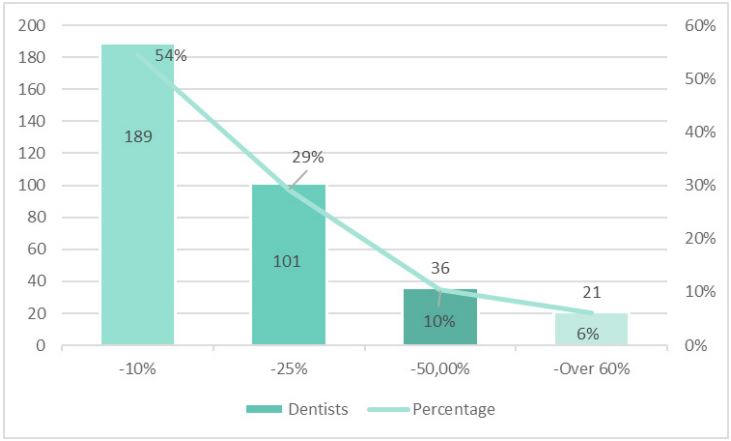

During the pandemic, and especially during the first period of containment, there was a general decline in the number of patients routinely attending a dental clinic, with about 74% of practitioners reporting a decrease in patients of between 10 and 25%, although in other practitioners (10.37%) the decrease during the first phase of the state of alert was close to 50% (Figure 3).

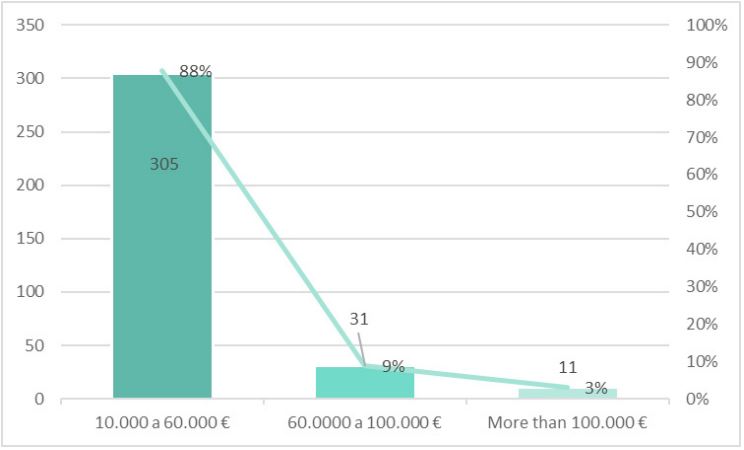

As regards the analysis of the economic impact on their income, 87.90% of Galician dental professionals reported a decrease in income of between 10,000 euros and 60,000 euros. (Figure 4).

Analysis of emotional state

The analysis of the 16 items is shown in Table 2, the most representative results being the following.

Table 2: Questionnaire on emotional state.

| Mean | Standard deviation | Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 1. Do you feel you are contributing to improving the current pandemic situation? | 2,09 | 1,03 | 10% | 20% | 22% | 49% |

| 2. Have you been disappointed in your dental work because of the conditions due to COVID-19? | 1,42 | 0,93 | 18% | 35% | 31% | 15% |

| 3. Has working with PPE made it more difficult to carry out your daily activity? | 2,16 | 1,01 | 9% | 19% | 26% | 46% |

| 4. Do you feel demotivated to come to the clinic on a daily basis? | 1,18 | 0,95 | 27% | 38% | 23% | 12% |

| 5. Do you feel emotionally drained at the end of the working day? | 1,91 | 0,95 | 10% | 26% | 33% | 32% |

| 6. Do you think patients' expectations, demands and moods have changed? | 2,26 | 0,75 | 2% | 15% | 41% | 42% |

| 7. Do you feel more sensitive to patients' criticisms of your treatments? | 1,52 | 0,97 | 17% | 33% | 33% | 17% |

| 8. Have you felt alone in dealing with the pandemic? | 1,68 | 1,07 | 18% | 30% | 25% | 28% |

| 9. Have you lost interest in dentistry since the pandemic began? | 0,87 | 0,95 | 44% | 31% | 17% | 8% |

| 10. Have you considered leaving the profession temporarily? | 0,57 | 0,87 | 62% | 20% | 12% | 6% |

| 11. Do you feel supported by the rest of your team for the measures (change in timetables, change in contracts, temporary redundancies, etc.) you have had to adopt to deal with the pandemic and its economic conse- quences? |

2,18 | 0,97 | 9% | 15% | 29% | 47% |

| 12. Has the pandemic also given you a new outlook on your life? | 2,25 | 0,85 | 5% | 13% | 35% | 48% |

| 13. Would you like to make profound changes in protocol management and human resource management? | 1,63 | 0,96 | 12% | 31% | 34% | 23% |

| 14. Have you ever cried or experienced a sense of despair during the pandemic? | 1,01 | 0,95 | 36% | 30% | 26% | 8% |

| 15. Have you ever felt the need to make a radical change in your life? | 1,56 | 1,08 | 23% | 22% | 33% | 23% |

| 16. Has your emotional life changed substantially during the pandemic? | 1,65 | 1,00 | 14% | 28% | 32% | 25% |

71% of the professionals considered that they were contributing to the improvement of the pandemic situation, with those professionals who are married or have a stable partner (p=0.008), those professionals who are personally in charge of managing administrative problems and those who usually make decisions (p=0.002) together with those professionals who have reduced the number of patients in their clinics (p=0.001), being the ones who have most perceived their involvement in the improvement of the pandemic situation.

72% felt that working with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) made their clinical activity more difficult. The difficulty was greatest in clinics that had lost patients and in clinics where there had been staff reductions.

The feeling of exhaustion at the end of the working day was predominant in 65% of the professionals, with female dentists once again being those who had the greatest perception (p=0.002).

With regard to the attitude of patients, 83% stated that the demands, expectations and mood of patients had changed, while 50% of the professionals responded that they felt more sensitive to patients’ criticisms of their treatments and to a greater extent the dentists who have less decision-making power (p=0.005) and management of their clinics.

In general, dentists in Galicia have not lost interest in dentistry and have not considered leaving the profession, with the exception of those working in clinics that have seen a large drop in the number of patients.

The feeling of loneliness is common among dentists and with statistical significance among clinics that have suffered a reduction in patients and those professionals who manage their clinics on a daily basis.

In the survey results, there is also a clear tendency to consider that the pandemic has brought a new outlook on life for many professionals, represented by 83%, being significant among female dental professionals (p=0.012).

56% responded that they had felt the need to make a radical change in their lives, with separated or divorced professionals being the group that most often considered this circumstance (p=0.003) and those professionals who have less decision-making power in their clinics.

Finally, the questionnaire analysed whether the emotional life of these professionals had changed substantially, and this was clearly expressed in 57% of the cases. Among this percentage, it stood out that female dentists had experienced a more intense modification in their emotional life (p=0.010); in the same way as those who are separated or divorced (p=0.001); and with those with fewer years of professional practice (p=0.021). Similarly, those dentists who rarely manage or make decisions in the practice have suffered more emotionally, along with the professionals who have suffered the most severe drop in income (over 100,000 euros).

Discussion

Dentists have faced many challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, affecting their physical and mental health, family relationships and financial status, with the added pressure of radically changing their professional protocols.

Most countries have suffered these consequences significantly and very few have had a low impact as reported by Mekhemar, et al. [9], in their study on the German population, justifying this low impact on the information received by professionals from their government and the financial support provided.

In the dental clinics, it was necessary to drastically modify the action protocols, incorporating individual protection measures, adapting the number of working hours and even reducing the number of collaborators and auxiliary staff.

The use of PPE influenced aspects such as concern about lack of supply, greater economic investment, difficulty in communicating with patients, and consequently an impact on emotional state.

Galician dentists overwhelmingly reported that the use of PPE had made it more difficult for them to perform their daily activities, findings that are in line with those observed by Malandkar et al. [10], 85% of whom agreed that wearing PPE affected their work efficiency, and 89% experienced difficulties in communication.

Another aspect related to PPE was the difficulty of procurement that occurred in most countries. This led some professionals to consider leaving their profession, as reflected by Pacutova et al. [11], Cole et al. [12], and Vick [13]. These findings contrast with those found in this study in which the questionnaire determined that interest in their profession or the possibility of leaving it was a minority response among the respondents. These findings could be explained by the fact that the number of dental professionals in Galicia was not very high in relation to other Spanish regions, and the supply of PPE was adequate. Galicia also had more time to organise itself, as the first wave arrived later and fewer people were affected, compared to other regions in Spain, so it had more information about the impact of COVID-19.

The increase in the number of working hours, together with the drastic modification of patient care protocols, especially over time, are factors to be taken into account in the increase of anxiety and stress, which can worsen interpersonal relations in consultations [14]. It is logical to think that the transformation of protocols in dental clinics was carried out in a short space of time, without the existence of evidence-based regulations, with explicit pressure from patients who demanded all kinds of safety and with no real time for professional teams to adapt to the new situation.

A relationship was found between the level of anxiety and decision-making and practice management. Those dentists who usually have control of management and decision making suffered less anxiety than those who do not have management responsibilities. A higher decisional self-esteem and sense of personal achievement helps in suffering less anxiety about decisions made and gaining a greater sense of job accomplishment [15].

Another unavoidable consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the impact on the financial status of professionals as a result of reduced activities with fewer daily appointments and higher investments in adapting to a new clinical environment with new preventive protocols, which has had an impact on their emotional state [16-18].

Tysiąc-Miśta et al. [19], in a study of Polish dentists, highlight the negative impact on the economic aspect, as do Shinde et al. [20], who report that most dentists in India reported a considerable impact on financial concerns with both emotional and professional repercussions.

The studies by Chamorro-Petronacci et al. [21], despite being very similar to ours in terms of the number of dental professionals and age, do not reflect the economic reality that appears in this study, with very different figures. These authors found that almost 60% of the professionals had experienced an estimated decrease in income of between 1,000 and 10,000 euros, a far cry from the 87.9% of our professionals surveyed who estimated a decrease in income of between 10,000 and 60,000 euros. It is evident that this difference in the ranges of losses could be justified by the fact that the costs of dental surgeries increased progressively throughout the successive waves of the virus, clearly reducing the profitability of these surgeries.

In another study conducted in Germany by Wolf et al. [8], whose sample is very similar to ours, dental practices with 1 to 4 practitioners were less affected by the economic impact of COVID-19 compared to larger practice structures, with personnel expenses being the largest cost element at 40% and the increase in the average monthly cost of materials due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the findings of another study conducted in Iraq by Mahdee et al. [22], economic losses in dental clinics in Iraq amounted to about 50% due to reduced working days, rescheduling of appointments to see only emergency cases, lack of government support, adaptation to practice modification and reduction of overall income. This has resulted in high levels of anxiety for all dentists. The authors’ observations and assessment of the current situation suggest that the costs of providing dental treatment increased due to the extra use of PPE, and longer waiting times due to the need for segregation of patients in the waiting rooms, which reduces the number of patients seen on a daily basis.

Another comparative study between self-employed private health workers and workers employed in the public health system [23], indicates that the self-employed had a problem of material resources that were not available at the beginning of the pandemic, and there was an increase in the cost of preventive material (masks and gloves) and this had to be paid for by the self-employed. This created mental stress for the self-employed and anxiety was higher in the first wave due to the closure of their private practices and, consequently, a sharp decrease in their income. Self-employed workers in the private sector have maintained a high level of anxiety and have been able to perceive their situation as difficult without receiving the media coverage of public health professionals.

Furthermore, the stigmatisation of health professionals has been a worrying situation worldwide for years and increased during this pandemic, both verbally and physically [24,25].

This circumstance, as pointed out by Ghareeb et al. [26], can be perpetrated by family members or patients themselves, finding in their study that the most prevalent verbal violence was shouting (90.48 %) and threats of harm (58.57 %), while pushing (91.67 %) and hitting (80.83 %) were the predominant types of physical violence.

Specific studies on dentists, such as that of Rhoades et al. [27], indicate that this professional group has experienced aggression at some point in their career, in the form of physical (45.5%), verbal (74%) and reputational aggression (68,7%).

Bitencourt et al. [28], recently identified predictors of stigmatisation in Brazilian healthcare workers, concluding that 47.6% reported situations of violence during the pandemic and that the most relevant and significant risk factors were: Not having children or a partner, less than 20 years’ experience, and working more than 36 hours a week.

In this study, no physical aggression was observed, but it was found that patient criticism of their professional activity had a much more negative impact than in other circumstances, with younger professionals being more likely to report this situation.

Studies conducted by Pai S et al. [29], during the pandemic have shown that mental health problems among health care workers require institutional reforms, along with early care and support. The work-life balance of professionals is the key to better efficiency and was greatly affected during the COVID-19 pandemic confinement period due to sudden and unexpected changes. In our study, the average number of hours worked ranged between 40 and 50 hours and more than half of them in two shifts, leading to a desire for profound changes in protocol management and human resources management, with a significant relationship among professionals where it was necessary to change the staffing Table (0.007) and among those who have suffered a significant drop in income (0,001). These data indicate the weakest links in the profession, requiring greater preparedness to meet new challenges to protect the wellbeing of dental teams and oneself and to maintain the workforce in the face of any future emergencies or pandemics.

Another study conducted by Vilar-Palomo et al, in Spain during the pandemic among podiatrists [30], obtained similar results to our study. They concluded that they have suffered a high level of anxiety due to the economic impact of COVID-19 as they are self-employed.

Finally, it is unquestionable that the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the mental health of a significant proportion of health professionals, including dentists, which may differ slightly from country to country, but which has led to a reduction in the resilience of these professionals and that this study, like others, should serve to better prepare for future pandemics and, as Mira et al. point out [31], raise awareness among government institutions to more effectively support all private health professionals and improve the skills of professionals to cope with difficult situations with better working protocols and focus on strategies for dealing with future emergencies of this kind.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic, as in other countries, had a professional and emotional impact on dentists. The implementation of new prevention measures and protocols did not cause major difficulties among Galician dentists; however, the professional activity carried out until then was affected in terms of their schedules and in the number of patients, which had an economic and employment impact on most of them. The pandemic has brought a new outlook, the need to review professional protocols, and changes in professional and personal life. This experience should help health authorities and dentists to act more effectively in future situations similar to that of COVID-19.

References

- Pulido-Fuentes M, González LA, Reneo IA, Cipriano-Crespo, C, Flores-Martos, et al. Towards a liquid healthcare: Primary care organisational and management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic-A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022; 22: 665.

- Pulido-Fuentes M, González LA, Reneo IA, Cipriano-Crespo C, Flores-Martos, et al. Towards a liquid healthcare: Primary care organisational and management strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic-A qualitative study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022; 22: 665.

- Campos-Mercade P, Meier AN, Schneider FH, Wengström E. Prosociality predicts health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Econ. 2021; 195: 104367.

- Wu F, Ren Z, Wang Q, He M, Xiong W, et al. The relationship between job stress and job burnout: The mediating effects of perceived social support and job satisfaction. Psychol. Health Med. 2021; 26: 204-211.

- Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Leon-Perez JM, Pignata S, Topa G, et al. Emerging Issues in Occupational Disease: Mental Health in the Aging Working Population and Cognitive Impairment-A Narrative Review. Biomed Res. Int. 2020; 2020: 1742123.

- Tysiąc-Miśta M, Dziedzic A. The Attitudes and Professional Approaches of Dental Practitioners during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17: 4703.

- Wolf TG, Zeyer O, Campus G. COVID-19 in Switzerland and Liechtenstein: A Cross-Sectional Survey among Dentists’ Awareness, Protective Measures and Economic Effects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17: 9051.

- Wolf TG, Deschner J, Schrader H, Bührens P, Kaps-Richter G, et al. Dental Workload Reduction during First SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Lockdown in Germany: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021; 18: 3164.

- Mekhemar M, Attia S, Dörfer C, Conrad J. Dental Nurses’ Mental Health in Germany: A Nationwide Survey during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021; 18: 8108.

- Malandkar V, Choudhari S, Kalra D, Banga P. Knowledge, attitude and practice among dental practitioners with regard to overcoming the barriers created by personal protective equipment in the COVID-19 era and delivering effective dental treatment: A questionnaire-based cross-sectional study. Dent. Med. Probl. 2022; 5: 27-36.

- Pacutova V, Madarasova Geckova A, Majernikova SM, Kizek P, de Winter, et al. Job Leaving Intentions of Dentists Associated With COVID-19 Risk, Impact of Pandemic Management, and Personal Coping Resources. Int. J. Public Health. 2022; 67: 1604466.

- Cole A, Ali H, Ahmed A, Hamasha M, Jordan S. Identifying Patterns of Turnover Intention Among Alabama Frontline Nurses in Hospital Settings During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021; 14: 1783-1794.

- Vick B. Career satisfaction of Pennsylvanian dentists and dental hygienists and their plans to leave direct patient care. J. Public Health Dent. 2016; 76: 113-121.

- Campos JADB, Martins BG, Campos LA, de Fátima Valadão-Dias F, Marôco J. Symptoms related to mental disorder in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 2021; 94: 1023-1032.

- Chipchase SY, Chapman HR, Bretherton R. A study to explore if dentists’ anxiety affects their clinical decision-making. Br Dent J. 2017; 222(4): 277-290.

- Sethi BA, Sethi A, Ali S, Aamir HS. Impact of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic on health professionals. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020; 36: S6-S11.

- Barabari P, Moharamzadeh K. Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Dentistry-A Comprehensive Review of Literature. Dent. J. 2020; 8: 53.

- Izzetti R, Nisi M, Gabriele M, Graziani F. COVID-19 Transmission in Dental Practice: Brief Review of Preventive Measures in Italy. J. Dent. Res. 2020; 99: 1030-1038.

- Tysiac-Mista M, Dziedzic A. The Attitudes and Professional Approaches of Dental Practitioners during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Poland: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17: 4703.

- Shinde O, Jhaveri A, Pawar AM, Karobari MI, Banga KS, et al. The Multifaceted Influence of COVID-19 on Indian Dentists: A CrossSectional Survey. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022; 15; 1955-1969.

- Chamorro-Petronacci C, Martin Carreras-Presas C, Sanz-Marchena A, Rodríguez-Fernández MA, Suárez-Quintanilla JM, et al. Assessment of the Economic and Health-Care Impact of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) on Public and Private Dental Surgeries in Spain: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020; 17: 5139.

- Mahdee AF, Gul SS, Abdulkareem AA, Qasim SSB. Anxiety, Practice Modification, and Economic Impact Among Iraqi Dentists During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020; 7: 595028.

- Pabón-Carrasco M, Vilar-Palomo S, Gonzalez-Elena ML, RomeroCastillo R, Ponce-Blandon JA, et al. Comparison of the Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Self-Employed Private Healthcare Workers with Respect to Employed Public Healthcare Workers: Three-Wave Study during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain. Healthcare (Basel). 2022; 11(1): 134. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11010134.

- Thornton J. Violence against health workers rises during COVID-19. Lancet. 2022; 400: 348.

- Taylor S, Landry CA, Rachor GS, Paluszek MM, Asmundson GJG. Fear and avoidance of healthcare workers: An important, underrecognized form of stigmatization during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020; 75: 102289.

- Ghareeb NS, El-Shafei, DA, Eladl AM. Workplace violence among healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic in a Jordanian governmental hospital: The tip of the iceberg. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021; 28: 61441-61449.

- Rhoades KA, Heyman RE, Eddy JM, Haydt NC, Glazman JE, et al. Patient aggression toward dentists. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2020; 151: 764-769.

- Bitencourt MR, Alarcão ACJ, Silva LL, Dutra AC, Caruzzo NM, et al. Predictors of violence against health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021; 16: e0253398.

- Pai S, Patil V, Kamath R, Mahendra M, Singhal DK, et al. Equilibrio entre la vida laboral y personal entre los profesionales de la odontología durante la pandemia de COVID-19: Un enfoque de modelado de ecuaciones estructurales. PLoS Uno. 24 de agosto de. 2021; 16(8): E0256663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256663.

- Vilar-Palomo S, Pabón-Carrasco M, Gonzalez-Elena ML, RamírezBaena L, Rodríguez-Gallego I, et al. Assessment of the Anxiety Level of Andalusian Podiatrists during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Increase Phase. Healthcare (Basel). 2020; 8(4): 432. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8040432.

- Mira JJ, Carrillo I, Guilabert M, Mula A, Martin-Delgado, et al. Acute stress of the healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic evolution: A cross-sectional study in Spain. BMJ Open. 2020; 10: e042555.