Research ArticleOpen Access, Volume 2 Issue 3

‘It Feels Like a Campaign for an Election’-Somali-Led Green Social Prescribing

Allport Tom1,2*; Jacobs Gali1,3; Musse Samira4 ; Natasha Bradley5

1Centre for Academic Child Health, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, UK.

2Community Children’s Health Partnership, Sirona Care & Health, Bristol, UK.

3University of Sheffield Medical School, Sheffield, UK.

4Barton Hill Activity Club, Bristol, UK.

5School of Nursing and Midwifery, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, UK.

*Corresponding author: Allport Tom

Centre for Academic Child Health, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, UK.

Email: tom.allport@bristol.ac.uk

Received : Apr 26, 2024 Accepted : May 09, 2024 Published : May 16, 2024

Epidemiology & Public Health - www.jpublichealth.org

Copyright: Tom A © All rights are reserved

Citation: Tom A, Gali J, Samira M, Bradley N. ‘It Feels Like a Campaign for an Election’-Somali-Led Green Social Prescribing. Epidemiol Public Health. 2024; 2(3): 1050.

Abstract

Introduction: Green (nature-based) social prescribing has potential to reduce health inequalities, but may require additional investment to work effectively with marginalised populations. Commissioners need evidence about effectiveness and mechanisms of change to tailor implementation.

Methods: We studied what works, for whom, and why, within a Somali-led green social prescribing intervention with disadvantaged refugee, migrant and ethnically diverse families and communities, funded through England’s National Health Service ‘Test and Learn’ green social prescribing initiative. Informed by realist evaluation, this involved ethnographic observations and participant interviews (n=8), followed by interviews (n=2) as part of iterative co-production process with programme providers.

Results: We describe three interconnected mechanisms for generating social connection and wellbeing: local and cultural knowledge enables confident outreach to isolated community members; an inclusive, non-judgmental, and solution-focused approach helps develop self-care skills, destigmatising mental health; nature-based activities help participants experience safety and connection outdoors.

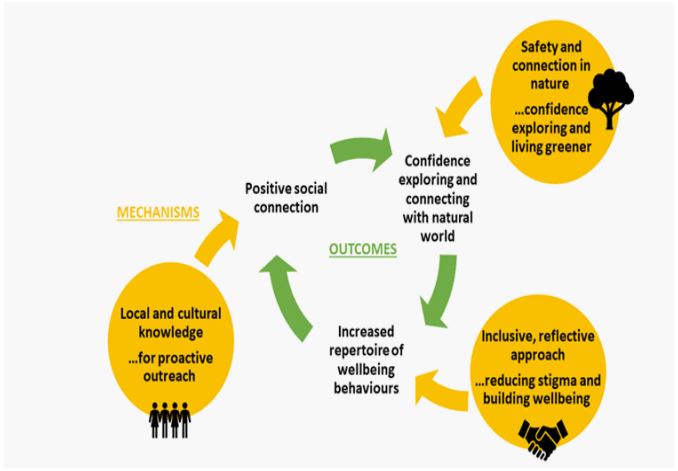

Conclusion: This intervention initiates positive social connection, confidence exploring nature, and an increased repertoire of wellbeing behaviours. The findings explain how skilled community assets and nature-based opportunities can counter marginalising and isolating processes by instigating a sustainable ‘virtuous cycle’ of mutually reinforcing outcomes.

Keywords: Green social prescribing; Nature; Emigration/Immigration; Somali; Resilience; Community participation.

Introduction

Ethnically diverse communities experience unequal access to mental health services [1], with additional barriers for refugees and forced migrants, who are some of the least likely groups to receive effective support or timely access to mental health interventions within the NHS, despite evidence of great need [2- 4]. The Coronavirus pandemic and associated social restrictions negatively impacted the mental health of migrant populations in the UK [5,6]. Multiple lockdowns highlighted the importance of inequalities of access to green space for wellbeing [7,8].

Social prescribing has great potential to help people experiencing stress, distress and/or social isolation, however funding has been rolled out with a limited evidence base for delivery and evaluation [9-12]. Multiple factors may influence the success of social prescribing initiatives [13,14]. Social prescribing in communities where there is deprivation, disadvantage or marginalisation may require additional investment and tailoring, as relevant services may not exist locally, or not feel safe and accessible [15,16].

“Green”, or “nature-based” prescribing has potential for reducing inequalities in wellbeing and connection to the natural world [17-21]. In nature-based social prescribing interventions, it is relevant that the activity offered is meaningful, enjoyable, challenging, forward looking, and incorporates appropriate therapeutic elements [22]. Facilitators’ skill in flexibly and reflexively providing the service, the continuity of the setting, and presence of peer support also appear important [23].

The NHS England Green Social Prescribing ‘Test and Learn’ scheme [24,25], aided by Sport England’s ‘Tackling Inequalities Fund’, has funded a range of initiatives in Inner City and East Bristol working with diverse communities, with projects led by a range of community groups. To continue this innovative way of working, commissioners need evidence about effectiveness and mechanisms of change.

To explore potential for effectiveness, social prescribing interventions need to be understood within their context [26]. Somali people constitute one of the largest diasporas of forced migration in the world, estimated at over 2 million [27], following political instability, persecution and violence in Somalia in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In Bristol, Somali births have increased 8-fold since the late 1980s [28]; at least 5% of children are now Somali [29]. Forced migration and subsequent experiences of social isolation/exclusion and discrimination have profound consequences for family structure and parenting [30]. Refugee children and families’ wellbeing and resilience depend on interconnected factors [31], with social connectedness or isolation playing a key role [32,33].

Multiple factors may influence the early developmental opportunities and experience of children in Somali migrant families [34], which may in turn contribute to difficulties experienced by Somali youth [35,36]. Somali community members have experienced multiple challenges from the Pandemic [37,38], with ongoing consequences for children and young people’s education and wellbeing. Social stigma can prevent mental health services being accessible to Somali and other ethnically diverse communities [39]. Like other disadvantaged and marginalised communities, Somali people may experience significant barriers to accessing green space, such as lack of local green space and degradation of the local environment [40].

We sought to evaluate a Somali-led green social prescribing intervention, delivered to disadvantaged ethnically diverse and migrant families and communities, aiming to understand how and why green social prescribing could be effective in engaging with and supporting this ethnically diverse and migrant community [41].

Materials and methods

Informed by realist evaluation [42], our research questions were:

• What is it about this green social prescribing project that works well?

• For whom does it work well for and why?

• What circumstances make for success?

• What barriers to success are faced by the project?

Methodology

Realist evaluation argues that nothing works everywhere for everyone- change produced by an intervention is dependent on the context to which the intervention was applied. The complexity of the social world means there is no one size fits all solution: observable change emerges within a specific context, from underlying mechanisms [43]. Realist evaluation aims to iteratively develop ‘programme theory’, which is evidence-based explanation of how and why an intervention works, for whom, in what circumstances. This is usually achieved through ‘contextmechanism-outcome configurations’ – these articulate specific interactions between intervention resources and intervention context, leading to mechanisms that generate outcomes (which may be multiple).

Green social prescribing is also unlikely to ‘work’ the same way for everyone. In this case, we focus on one particular green social prescribing project, which was tailored towards the needs of a socioeconomically deprived and marginalised community in Bristol.

The intervention

Green social prescribing events organised by Barton Hill Activity Club started in November 2021, supported by NHS England ‘test and learn’ funding allocated to Bristol North Somerset South Gloucestershire (BNSSG) Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and Sport England ‘Tackling Inequalities Fund’ via WESport. These lasted from 60 mins to a few hours depending on the activity. There were multiple sessions per week focused on different ages and demographics, some with a regular weekly schedule, and others as single events.

Data collection and analysis

An iterative approach was used to co-produce programme theory with the programme designers and recipients (i.e., green social prescriber providers and participants). Initial qualitative data collection took place between February and May 2022, involving participant observations and informal interviews (n=8) at the green social prescribing activities delivered by Barton Hill Activity Club between February and May 2022. Written informed consent was obtained prior to data collection.

Primary data collection took place at five activities: a trip to a City Farm, an arts & crafts session for children and families in a nearby park, a coffee morning for parents, a trip to a local historical attraction, the ship ss Great Britain, and a visit to a small woodland outside of the city.

Observations were informed by ‘focussed ethnography’ [44,45] and reflections were captured as fieldnotes. The primary researcher also kept a diary of experiences, senses, and decisions, to assist the team’s reflexive evaluation of data collection and analysis [46].

Interviews explored participant’s experience of the activities and focused on how their participation might be having a positive impact on parent and child wellbeing. Questions encouraged participants to consider relationships between project activities, significant people and contexts in their lives, and the outcomes generated [47]. Interviews were face to face and lasted approximately 30 minutes. Key quotes were integrated with fieldnotes immediately.

Data analysis initially coded fieldnotes and quotes to identify and organise insights related to context, mechanisms, or outcomes [48]. The themes generated from this analysis informed construction of an Initial Programme Theory (IPT) on what works, for who, and why. Additionally, the ‘VICTORE’ checklist [49] was used to unpack programme complexity and identify areas where further understanding was needed, to inform subsequent discussions with stakeholders (Appendix A).

The IPT was then used to inform a semi-structured interview schedule (Appendix B). A semi-structured interview was undertaken by video with 2 lead providers of the intervention, which allowed us to further develop and refine the IPT. This interview lasted one hour and was recorded and transcribed. After further refinement, the main proposals of the IPT were presented to the programme providers, in the form of a set of ‘Findings: What did we learn?’ for further interview/discussion. Learning from this was then incorporated into the findings reported here.

The development of IPT as context-mechanism-outcome configurations [43] was supported by an experienced realist evaluation researcher, who audited aspects of both content and process in the analysis and assisted with the organisation of configurations. Findings are reported with detail of three context-mechanism-outcome configurations, alongside supporting quotes from interviews and fieldnotes.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Health Science Student Research Ethics Committee at the University of Bristol (Reference 10455).

Results

1. Findings indicate three explanatory processes (contextmechanism-outcome configurations) through which the intervention could have positive outcomes in the lives of participants: Local and cultural knowledge underpins confident, proactive outreach;

2. Inclusive approach to reducing stigma and improve wellbeing;

3. Safety, connection, and confidence in nature.

These are depicted as context-mechanism-outcome configurations in Table 1.

Table 1: Intervention processes (context-mechanism-outcome configurations).

| PROCESS | Local and cultural knowledge underpins confident, proactive outreach |

Inclusive approach to reducing stigma and improve wellbeing |

Safety, connection, and confidence in nature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context | Factors driving social isolation, mistrust, marginalisation |

Shame/stigma of mental health, and constraints on communication |

Restricted zone of perceived safety |

| Mechanism | Local and cultural knowledge for proactive outreach |

Inclusive, reflective approach reducing stigma and building wellbeing |

Safety and connection in nature bringing confidence exploring and living greener |

| Outcome | Positive social connection | Increased repertoire of wellbeing behaviours & self-care |

Connecting with the natural world, nearby and further afield |

Theme 1: Local and cultural knowledge underpins confident, proactive outreach

Providers’ strong local knowledge, connections, relationships and trust, and their understanding of culturally-familiar activities, of socially-isolating processes and experience, and of the powerful impact of the Coronavirus pandemic, gave them the ability and confidence to reach out to local families, regardless of their situation.

Context: Multiple factors driving social isolation, mistrust, marginalisation

This population is at risk of social isolation or exclusion due to multiple challenges, including loss of familiar cultural contexts and structures for childrearing, and the range of traumas and adversities experienced through forced migration, deprivation post-migration, stigma, and implicit or explicit racism. Negative experiences arising from these challenges contribute to lack of wellbeing, low confidence, mistrust, and/or avoidance of some social settings.

The pandemic appears to have been an exacerbating influence, with reduced wellbeing experienced especially for those living in confined housing, with little access to green space, for ethnically diverse groups, and for the socially isolated. The mental health impacts since the pandemic have continued to confer complex wellbeing and developmental challenges, leading to a vicious cycle of distress and social isolation in some situations.

‘We live in tower blocks, we’ve been cooped up inside so long. Covid made it a million times worse. You can’t stay indoors any more. Let’s be around other people we know’ (Participant).

‘Those people especially those with young children during the Covid are you know with the anxiety and the start of having depression and they’re like ‘if I’m stuck home one more month, I will lose it’ (Participant)

‘There’s not much going on in the area for that age I’ll be honest with you. We’re the only activity group that provide any activities for children… in the area that I know of’ (Provider)

Mechanism: Local and cultural knowledge for proactive outreach

The intervention facilitators have strong local knowledge, connections, relationships, and trust within their community. They understand culturally familiar activities, bringing ideas of what could work to engage community members. This gave them confidence in the importance and acceptability of persistence/perseverance to engage people experiencing social isolation and stigma. The intervention resources (funding and network) empowered them to reach out to local families, proactively, affirmatively, and persistently. Providers paid attention to the range of needs of participants of different ages, and those in different situations. A regular schedule of weekly activities was offered which was easy for participants to plan around.

‘We, do so many different things for people like the elderly, the mums with young kids and children, the teenagers only… We can provide something for the kids and the mums at the same time. For the elderly ladies we went to [their homes] to let them know about sessions… We provided them a bus to get there. We find the time that suits them’ (Provider).

‘Some people will come over, and some won’t so it’s all about approaching people and telling them who you are and what you’re doing, calling them one by one-you need to be there today, you’re coming out today!, they were so cautious at first saying like ‘what is this’ and ‘why are we here’, but now they look forward to it. They are asking ‘when is the next session?’ all the time’ (Provider).

‘The coordinators’ role is calling people from their houses to come one by one and say “you need to come out today!”. it’s on a daily basis. Reminding them constantly. Yeah it feels like a campaign for an election’ (Provider).

Outcome: Positive social connection

Positive experiences of social interaction and connection increase self-confidence in the ability to socialise and make new connections, igniting an iterative, potentially self-sustaining process towards social inclusion and effective community-building. Connections within the intervention supported families to identify other helpful services and overcome bureaucratic challenges.

‘I’ve expanded my friendship circle since coming on more trips. I really like the mothers’ sessions when the kids are busy at school, it gives me more time to socialise with other mums and just chat about all sorts of things’ (Participant).

‘We just go to the park and chat with mums and just have a big gathering and now they start to bring hot drinks and fruit. It just grew and grew, the children can run around, and they can talk to one another’ (Provider).

‘They were asking so many questions at the beginning but now they’re the ones answering each others questions for us. They tell other people who aren’t involved about what they are doing you know, so new faces then keep coming each week’ (Provider).

The women [were] really enthusiastic about this sort of initiative being able to carry on for longer (Observation from field notes).

Theme 2: Inclusive approach to reducing stigma and building wellbeing

Facilitators worked proactively to involve children, young people, and parents/carers through the variety of activities they provided, differentiated to differing needs and interests, translating between languages where required. They supported reflective, solution-focused discussions incorporating positive ways to speak about wellbeing and mental health, serving to destigmatise, build self-care skills and open pathways to improved wellbeing. They offered creative, enjoyable, free activities that appeared to engage and enrich the experience of a wide variety of participants.

Context: Shame/stigma of mental health, and constraints on communication

Families require nourishing, supportive community relationships to develop and maintain a sense of belonging. In a closely connected migrant community, fear of judgement by others about difficulties in people’s lives, and other forms of shame or stigma, may powerfully obstruct families’ opportunities for social interaction. Low trust in public services further contributes to stress and social isolation.

This intervention has developed within a longstanding relationship of co-production between community members, community organisation, and academic partners, with a high degree of trust between collaborators and a shared perspective on the complex causes of distress and stigma within these communities. This conferred credibility to and knowledgeability of the target audiences.

‘Something happened with [one parent’s] children. There was some rumours going around and it’s not a nice feeling to know that people are talking behind your back or whispering as you passing by. A few incidents happened in the community so she isolated herself. She told me that she finds it really difficult to live in this area. She was like ‘I’m not coming I don’t want to be anywhere around this community I don’t like it.’ (Provider)

‘Nobody would be turning up if you don’t have a [good] reputation it’s as simple as that. People are knowing us now, they’re like “oh Barton Hill Activity Club I’ve heard about you.’ (Provider)

Mechanism: Inclusive, reflective approach reducing stigma and building wellbeing

The intervention offered creative, imaginative, free, fun, and non-competitive activities, to enrich nature-based experiences. Providers paid attention to the range of Participants’ needs, especially in relation to confidence and social connectedness, for example those cautious about social situations could be given additional support in advance. Facilitators used an inclusive, accessible, reflective, and solution-focused approach to encourage conversations about wellbeing while these activities were taking place. Care was taken to ensure conversations were nonjudgemental and acknowledged individuals’ concerns.

Everyone who came was really excited to be there and this energy filtered through to the whole group. [The Providers] kept in touch with everyone, which created a really cohesive atmosphere. Lots of families coming together, maybe acted as motivation for others to join who might have been hesitant. The more, outgoing women of the group make a real effort to include the more quiet and reserved members into conversations. (Observations from field notes)

‘Someone suggested, can you invite her [an isolated community member with children]?. I just wanted to make sure that she felt safe. I said “if you just come one day and if you don’t like it you can walk out simple as that” so she said “okay I’ll come just for you” and she came and now I just seen her this morning in the park and she was like “when is the coffee morning coming back?” (Provider)

‘We make sure it’s a safe environment, and everyone has to follow that rule, you know if you give mutual respect for each other than that becomes a safe place.’ (Provider)

Outcome: Increased repertoire of wellbeing behaviours

Participants experienced positive nature-based activities as part of the group. Being invited to share, and reflect on how these experiences made them feel, opened up further discussion about ways to develop and maintain wellbeing. This encouraged participants to be reflective and solution-focused regarding self-care skills. These conversations developed over time, such that the intervention served to destigmatise issues of wellbeing and mental health.

‘You definitely need to take care of yourself in order to look after your children and family otherwise who else will do it, its nice for the community to remind you to do that’ (Participant).

‘Everyone was just talking about what was going on around them, what is happening, what are their worries and the conversation, it was amazing to listen to it’ (Provider).

‘It makes me happy to see them all run over and asking lots of questions’ (Participant).

‘One lady [started] to discuss well-being and the ways in which we all individually look after ourselves. Everyone engaged in this chat and all shared opinions and methods on self-care. In this session I became aware of how much being part of the club positively changed the way people viewed well-being’ (Observation from field notes).

Theme 3: Safety and connection in nature

Green social prescribing activities appeared to open participants to a variety of benefits of nature-based experience and activity, to help them experience natural environments as accessible, connected with their lives, and engaging their curiosity and imagination.

A key challenge to the success of green social prescribing activities with these communities appeared to be families’ perception of appropriate weather conditions for attending outdoor activities. Providers reported a differential between the significance of this for parents and children, with children & young people more willing to attend activities on cold or wet days than their parents. They adapted the activities they provided to by temporary structures for example tents or alternative indoor activities planned, whilst maintaining a nature-based focus where possible (e.g. using virtual reality or nature-based arts activities).

Context: Restricted zone of comfort and safety

Coming out of pandemic restrictions, parents/carers and young people had concerns about the legitimacy and safety of social contact, especially indoors. The comparatively less hospitable outdoors in Northern Europe means that migrants and refugees may be concerned about cold or wet weather, muddy conditions, and related risk to them-selves or their children. Experiences of marginalisation and racism outside of the local area contribute to fear and a restricted ‘comfort zone’.

‘The absence of good weather conditions turns people off coming. lots of community members are from places with a hot climate and so the UK weather is in contrast to what they’re used to’ (Provider).

‘They’ve been cooped up inside because of the storm. It’s extremely difficult to be in green spaces everyday when you live in a tower block, so the opportunity is a welcome one’ (Participant).

I noticed a lot of families arriving together to the site and people following each other in cars, travelling together away from their usual area might feel safer that way (Observation from field notes).

Mechanism: Safety and connection in nature bringing confidence exploring and living greener Facilitators understood specific challenges for outdoor, nature-based activities for migrant and ethnically-diverse families, which enabled them to design outdoor social activities that felt safe and attractive to participants. Their awareness of local zones of confidence for participants from resource-poor ethnically diverse & migrant communities allowed them to provide activities that were accessible, at the same time serving to enlarge participants’ ‘comfort zones’ for exploring more widely. This included the local area, as well as excursions to other habitats within and outside the city, and visiting or erecting temporary structures for adverse weather. Outdoor social activities were offered that felt safe at a point of emergence from pandemic restrictions.

The facilitators were established community members, not nature experts, which meant they used language and activity that made sense to the people involved.

‘It’s cold but when my kids saw the tent being put out from our flat window they dragged me out to come with them…I am freezing but it’s nice to see some familiar faces who I’ve not seen in a while’ (Participant).

Many parents said they have lived in Bristol for many years but have never been able to see this cultural landmark… they explained how with busy lives it’s extremely difficult to make time to plan a trip like this and make sure its somewhere safe and fun for the kids to come… this group has made it possible (Observation from field notes).

‘They don’t see nature. I’ve noticed how much families need these sessions- they don’t have that connection with nature, they don’t see it as applying to them. This helps them see it as accessible, something that relates to them’ (Provider).

Outcome: Connecting with the natural world, nearby and further afield

Participants had positive experiences of spending time in nature. This brought recognition that green space has public value and can be a regular part of their lives (in contrast to being private property or an exclusive amenity only for host communities). Participants gained from deeper connection to nature as part of their daily lives, by understanding the natural environment to be accessible to them. Undertaking these activities as part of a social group builds confidence in exploring wider areas of the city and its surroundings, reducing marginalisation.

‘We all need to recharge our batteries as life can get overwhelming, engaging in varied activities helps to lift up low moods, going to a farm to walk and connect with people can remind you to take care of yourself’ (Participant).

‘It feels really good to see all of the kids come out… and I can tell they’re really excited to see something new in their own local park’ (Participant).

‘The kids obviously love it. Its somewhere that’s so different to our usual surroundings, it feels like a ‘real break’ from daily life’ (Participant).

Discussion

Summary

We report the potential mechanisms of change offered by a Somali-led green social prescribing intervention in a UK city. This describes an iterative process towards more social connection and wellbeing; an inclusive, non-judgmental, reflective, and solution-focused approach helping develop self-care skills and destigmatise mental health; and nature-based activities that helped participants see their natural environment as accessible and a part of their lives, widening marginalised community members’ ‘comfort zones’ in the world around them.

Strengths and limitations

This study has been developed from within a ten-year collaborative relationship between practitioners and researchers, seeking understanding and change for a marginalised migrant community. The evaluation described here gathered data from multiple sources – observations, informal interviews with participants and semi-structured interviews with providers. These findings contribute a rich, nuanced picture of the ways this intervention may contribute to positive changes in participants’ lives.

The study itself was time-bound, and took place within the framework of one intervention, and is therefore limited in both the scope of data collection and the potential for generalisability. However, its relevance within its context is assured by the iterative development of findings within long-term and trusting community-practitioner-researcher relationships.

Mechanisms of change

The initial programme theory reported here connects local, cultural knowledge to the delivery of inclusive self-care and nature-based activities, tailored towards a marginalised migrant and refugee community and including people of different age groups. This could be considered an exemplar of effective practice in addressing barriers to access to green social prescribing. The findings underscore the value of directing resources for green social prescribing via skilled local community groups, as part of a package of fairer investment in marginalised communities [34,50].

Furthermore, the mechanisms identified here – positive social connection, confidence exploring and connecting with the natural world, and increased repertoire of wellbeing behaviours -could interact and reinforce each other. We have theorised this as a ‘virtuous circle’, illustrated in Figure 1, in which the three processes enhance each other, therefore offering potential sustainability of the intervention. This potential for sustainability is worthy of further investigation in efforts to overcome the adverse circumstances experienced by migrants and refugees.

Comparison with existing literature

Green social prescribing has developed from a limited evidence base [51]. Our contribution has been to explain the intervention within a particular social and environmental context. Our findings are broadly consistent with others’, for example about the importance of trust, and the contribution to social engagement and community belonging [52-54]. Reports from agencies working with Somali communities around nature also describe building trust through cultural sensitivity and proactive engagement [55-57]. However, nature connection and access to urban green space is often overlooked during debates over migrant and refugee integration [57].

The present findings therefore have relevance for the development of ‘nature on prescription’ complex interventions [23], which seek to reduce inequalities of access through targeting and tailoring to often-marginalised populations, and to children and families [58-60]. We provide evidence in support of the added value of funding through community-led activity [61,62], to harness co-production within efforts to address the ‘wicked problems’ of health inequalities rooted in socioeconomic deprivation [63].

Implications for research and practice

This small-scale, local example helps to articulate the challenges, needs and solutions associated with green social prescribing interventions for marginalised populations and for families. Our findings depict how skilled community assets and resources and opportunities can address and counter marginalising and isolating processes, and offer potential to reduce health and wellbeing inequalities by instigating a ‘virtuous circle’ of mutually reinforcing outcomes [64]. Ripple effects could occur at the community and neighbourhood level through increased connectedness and belonging, and wider uptake of nature-based activities and self-care behaviours [65]. Our methodology offers a way to elaborate programme theory without major commitment of resources, drawing on the trust that comes from long-term collaboration.

Our findings could have broad relevance for the design of community-based interventions such as social prescribing, and for commissioning that seeks to reduce inequalities in health and wellbeing. Interventions that don’t understand marginalising and isolating processes are likely to worsen inequalities. Conversely, it may be highly effective to address socioeconomic contexts by investing in the resources that connect and include marginalised groups.

Signposting alone is an insufficient strategy - in socio-economically disadvantaged or marginalised communities, link workers need to be resourced and locally relevant social prescribing activities need to be commissioned.

We argue that empowering, legitimising and resourcing community groups may be a highly effective component of inequality-reducing commissioning. Single interventions will not address all aspects of adverse and unequal circumstances. For maximum impact, commissioners should consider how to enable social prescribing and other community-based projects to work in partnership, encouraging relationships between services and within the broader system.

Conclusion

We explain how a Somali-led green social prescribing intervention instigates an iterative process towards improved social connection and wellbeing. Skilled community groups and nature-based opportunities can counter marginalising and isolating contexts by connecting participants into a ‘virtuous cycle’ of mutually reinforcing outcomes. Providing the resource necessary to deliver co-produced, community-led social prescribing interventions may represent effective and sustainable opportunities to reduce inequality.

Declarations

Funding: This study received no specific funding. The green social prescribing work of Barton Hill Activity Club was funded by NHS England Green Social Prescribing ‘Test and learn’ work via Bristol, North Somerset & South Gloucestershire Integrated Care Board (BNSSG ICB) and Sport England ‘Tackling Inequalities Fund’ via WESport. N.B.’s role was funded by NIHR Research Capability funding, also via BNSSG ICB.

Acknowledgments: We thank Participants and Providers of Barton Hill Activity Club’s Green Social Prescribing programme.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Bansal N, Karlsen S, Sashidharan SP, Cohen R, Chew-Graham CA, et al. Understanding ethnic inequalities in mental healthcare in the UK: A meta-ethnography. PLoS Med. 2022; 19(12): e1004139. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004139.

- Tribe R. Mental health of refugees and asylum-seekers. APT. 2002; 8(4): 240-7.

- Aspinall PJ, Watters C. Refugees and asylum seekers: A review from an equality and human rights perspective. Research Report 52: Equality and Human Rights Commission. 2010.

- UNHCR. Mental Health and Psychosocial Support. Geneva: United Nations High Comission for Refugees. 2022. https://www.unhcr.org/mental-health-psychosocial-support.html.

- Orcutt M, Patel P, Burns R, Hiam L, Aldridge R, et al. Global call to action for inclusion of migrants and refugees in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020; 395(10235): 1482-3. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30971-5.

- Pinzon-Espinosa J, Valdes-Florido MJ, Riboldi I, Baysak E, Vieta E. Group EPABW. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Mental Health of Refugees, Asylum Seekers, and Migrants. J Affect Disord. 2021; 280(Pt A): 407-8.

- Holland F. Out of Bounds: Equity in Access to Urban Nature. Birmingham, UK: Groundwork. 2021. https://www.groundwork.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Out-of-Bounds-equity-inaccess-to-urban-nature.pdf.

- Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. COVID-19 mental health and well-being surveillance: Report. London: UK Government. 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-report.

- House of Commons Library. Research briefing: Social Prescribing. London: UK Parliament. 2020. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8997/.

- Bickerdike L, Booth A, Wilson PM, Farley K, Wright K. Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(4): e013384. DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013384.

- Husk K, Blockley K, Lovell R, Bethel A, Lang I, et al. What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A realist review. Health & social care in the community. 2020; 28(2): 309-24.

- Kiely B, Croke A, OShea M, Boland F, OShea E, et al. Effect of social prescribing link workers on health outcomes and costs for adults in primary care and community settings: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022; 12(10): e062951.

- Bertotti M, Frostick C, Hutt P, Sohanpal R, Carnes D. A realist evaluation of social prescribing: An exploration into the context and mechanisms underpinning a pathway linking primary care with the voluntary sector. Primary health care research & development. 2018; 19(3): 232-45.

- Pescheny JV, Pappas Y, Randhawa G. Facilitators and barriers of implementing and delivering social prescribing services: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018; 18(1): 86. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-018-2893-4.

- Mercer SW, Fitzpatrick B, Grant L, Chng NR, McConnachie A, et al. Effectiveness of Community-Links Practitioners in Areas of High Socioeconomic Deprivation. Ann Fam Med. 2019; 17(6): 518-25. DOI: 10.1370/afm.2429.

- Aughterson H, Baxter L, Fancourt D. Social prescribing for individuals with mental health problems: A qualitative study of barriers and enablers experienced by general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract. 2020; 21(1): 194.

- Garrett JK, Rowney FM, White MP, Lovell R, Fry RJ, et al. Visiting nature is associated with lower socioeconomic inequalities in well-being in Wales. Scientific Reports. 2023; 13(1): 1-13.

- Centre for Sustainable Healthcare. Green Social Prescribing for sustainable healthcare. 2021.

- Callaghan A, McCombe G, Harrold A, McMeel C, Mills G, et al. The impact of green spaces on mental health in urban settings: A scoping review. J Ment Health. 2021; 30(2): 179-93. DOI: 10.1080/09638237.2020.1755027.

- Markevych I, Schoierer J, Hartig T, Chudnovsky A, Hystad P, et al. Exploring pathways linking greenspace to health: Theoretical and methodological guidance. Environ Res. 2017; 158: 301-17. DOI: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.06.028.

- Van den Bosch M, Sang ÅO. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health–A systematic review of reviews. Environmental research. 2017; 158: 373-84.

- Garside R, Orr N, Short R, Lovell B, Husk K, et al. Therapeutic nature: Nature-based social prescribing for diagnosed mental health conditions in the UK. Final Report for DEFRA. 2020.

- Fullam J, Hunt H, Lovell R, Husk K, Byng R, et al. A handbook for nature on prescription to promote mental health. Exeter, UK: University of Exeter. 2021. https://www.ecehh.org/wp/wpcontent/uploads/2021/05/A-Handbook-for-Nature-on-Prescription-to-Promote-Mental-Health_FINAL.pdf.

- NHS England. Green social prescribing. UK Government Website. 2020.

- Haywood A, Dayson C, Garside R, Foster A, Lovell B, et al. National Evaluation of the Preventing and Tackling Mental Ill Health through Green Social Prescribing Project: Appendices to Interim Report-September 2021 to September 2022. 2023.

- Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. American journal of community psychology. 2009; 43(3-4): 267-76.

- Kleist N, Abdi MS. Global connections: Somali Diaspora practices and their effects. Rift Valley Institute. 2022. https://riftvalley.net/publication/global-connections-somali-diaspora-practicesand-their-effects

- Office for National Statistics. Parents country of birth, England and Wales. 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/parentscountryofbirthenglandandwales/previousReleases.

- Mills J. Community Profile - Somalis living in Bristol. Bristol, UK: Bristol City Council. 2014.

- Osman F, Klingberg-Allvin M, Flacking R, Schön U-K. Parenthood in transition–Somali-born parents experiences of and needs for parenting support programmes. BMC international health and human rights. 2016; 16(1): 1-11.

- Fazel M, Betancourt TS. Preventive mental health interventions for refugee children and adolescents in high-income settings. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2018; 2(2): 121-32.

- Salway S, Such E, Preston L, Booth A, Zubair M, et al. How can we reduce loneliness among migrant and ethnic minority people? Systematic, participatory review of programme theories, system processes and outcomes. Research Overview, Toolkit for practitioners, Interactive case studies. University of Sheffield. 2020.

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The lancet. 2020; 395(10227): 912-20.

- Allport T, Osman F. Find your village: A call for culturally-coordinated understanding and action. 2023 under review. https://drive.google.com/file/d/11erzgdwA0eLrDl3Aj5_aj93oE0v6dKHR/view?usp=drive_link.

- Osman F, Mohamed A, Warner G, Sarkadi A. Longing for a sense of belonging—Somali immigrant adolescents experiences of their acculturation efforts in Sweden. International journal of qualitative studies on health and well-being. 2020; 15(sup2): 1784532.

- Gillman P. The achievement of Somali boys: A case-study in an inner-London comprehensive school: University of Oxford. 2017.

- The Anti-Tribalism Movement. COVID-19 in the Somali community: Urgent briefing for policy-makers in the UK. 2020. https://www.councilofsomaliorgs.com/assets/COVID-19-Impact-onthe-Somali-Community.pdf.

- Bristol Somali Youth Voice and the Bristol Somali Forum. Impact of COVID-19 on Somali Community in Bristol. Bristol. 2020. https://www.bristolhealthpartners.org.uk/news/covid-19-hasworsened-the-inequalities-experienced-by-bristols-somalicommunity/.

- Linney C, Ye S, Redwood S, Mohamed A, Farah A, et al. Crazy person is crazy person. It doesnt differentiate: An exploration into Somali views of mental health and access to healthcare in an established UK Somali community. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2020; 19: 1-15.

- MacGregor S, Walker C, Katz-Gerro T. Its what Ive always done: Continuity and change in the household sustainability practices of Somali immigrants in the UK. Geoforum. 2019; 107: 143-53.

- Elliott M, Davies M, Davies J, Wallace C. Exploring how and why social prescribing evaluations work: A realist review. BMJ open. 2022; 12(4): e057009.

- Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic Evaluation: Sage. 1997.

- Greenhalgh J, Manzano A. Understanding contextin realist evaluation and synthesis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2022; 25(5): 583-95.

- Wall SS. Editor Focused ethnography: A methodological adaptation for social research in emerging contexts. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 2015.

- Knoblauch H. Editor Focused ethnography. Forum qualitative sozialforschung/forum: Qualitative social research. 2005.

- Ortlipp M. Keeping and using reflective journals in the qualitative research process. The qualitative report. 2008; 13(4): 695-705.

- Evans N, Whitcombe S. Using circular questions as a tool in qualitative research. Nurse researcher. 2016; 23(3).

- Wiltshire G, Ronkainen N. A realist approach to thematic analysis: Making sense of qualitative data through experiential, inferential and dispositional themes. Journal of Critical Realism. 2021; 20(2): 159-80.

- Pawson R. The science of evaluation: A realist manifesto: Sage. 2013.

- Hassan SM, Ring A, Goodall M, Abba K, Gabbay M, et al. Social prescribing practices and learning across the North West Coast region: Essential elements and key challenges to implementing effective and sustainable social prescribing services. BMC Health Services Research. 2023; 23(1): 1-14.

- Kondo MC, Oyekanmi KO, Gibson A, South EC, Bocarro J, et al. Nature prescriptions for health: A review of evidence and research opportunities. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020; 17(12): 4213.

- Sumner RC, Sitch M, Stonebridge N. A mixed method evaluation of the Nature on Prescription social prescribing programme. 2021.

- Simpson S, Furlong M, Giebel C. Exploring the enablers and barriers to social prescribing for people living with long-term neurological conditions: A focus group investigation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021; 21(1): 1230. DOI: 10.1186/s12913-021-07213-6.

- Coventry PA, Brown JE, Pervin J, Brabyn S, Pateman R, et al. Nature-based outdoor activities for mental and physical health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. SSM Popul Health. 2021; 16: 100934. DOI: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100934.

- Allport T, Grant M, Er V. Improving childrens opportunities for play, physical activity, and social interaction through neighbourhood walkabout and photography in Bristol, UK. Cities & health. 2023; 7(6): 1088-107.

- Leikkilä J, Faehnle M, Galanakis M. Promoting interculturalism by planning of urban nature. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2013; 12(2): 183-90.

- Rishbeth C, Blachnicka-Ciacek D, Darling J. Participation and wellbeing in urban greenspace:curating sociabilityfor refugees and asylum seekers. Geoforum. 2019; 106: 125-34.

- Diaz-Martinez F, Sanchez-Sauco MF, Cabrera-Rivera LT, Sanchez CO, Hidalgo-Albadalejo MD, et al. Systematic Review: Neurodevelopmental Benefits of Active/Passive School Exposure to Green and/or Blue Spaces in Children and Adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023; 20(5): 3958. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph20053958.

- de Bell S, Alejandre JC, Menzel C, Sousa-Silva R, Straka TM, et al. Nature-based social prescribing programmes: Opportunities, challenges, and facilitators for implementation. medRxiv. 2023: 2023.11. 27.23299057.

- Garside R, Lovell R, Husk K, Sowman G, Chapman E. Nature prescribing. British Medical Journal Publishing Group. 2023.

- He Y, Jorgensen A, Sun Q, Corcoran A, Alfaro-Simmonds MJ. Negotiating complexity: Challenges to implementing communityled nature-based solutions in England pre-and post-COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(22): 14906.

- Malby R, Boyle D, Wildman J, Omar B, Smith S. The Asset Based Health Inquiry: How best to develop social prescribing. 2019.

- Thomas G, Lynch M, Spencer LH. A systematic review to examine the evidence in developing social prescribing interventions that apply a co-productive, co-designed approach to improve wellbeing outcomes in a community setting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8): 3896.

- Allport T, Briggs H, Osman F. At the heart of the community – a Somali womans experience of alignment of support to escape social isolation in pregnancy and early motherhood. 2023. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1_Ca6zPltpdwRvKndXk_dsKvW9MgS4VuW/edit?usp=drive_link&ouid=112386517763632159506&rtpof=true&sd=true.

- Nobles J, Wheeler J, Dunleavy-Harris K, Holmes R, Inman-Ward A, et al. Ripple effects mapping: Capturing the wider impacts of systems change efforts in public health. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022; 22(1): 72. DOI: 10.1186/s12874-022-01570-4.