Research Article Open Access, Volume 1 Issue 1

Training of Health Care personnel on Obstetric Violence: An Experience in Togo using the Forum Theatre Technique

Alix Mathonnet1*; Philippe Arvis2

1Gynecology-Obstetrics Department, Women’s Mother Child Hospital, Hospices Civils de Lyon, France.

2Gynecology-Obstetrics Department, Clinique de la Sagesse, Rennes, France.

*Corresponding author : Alix Mathonnet

Gynecology-Obstetrics Department, Women’s Mother Child Hospital, Hospices Civils de Lyon, France.

Received : Aug 08, 2023 Accepted : Aug 31, 2023 Published : Sep 07, 2023

Epidemiology & Public Health - www.jpublichealth.org

Copyright: Mathonnet A. © All rights are reserved

Citation: Mathonnet A, Arvis P. Training of Health Care Personnel on Obstetric Violence: An Experience in Togo using the Forum Theatre Technique. Epidemiol Public Health. 2023; 1(1): 1002.

Abstract

Obstetrical Violence (OV) refers to all the disrespectful treatments and mistreatments inflicted on women during pregnancy and childbirth by health professionals. It can be physical, psychological or discriminatory, related to a lack of consent or respect, an abandonment of care or detention in the health structure in case of unpaid fees [1]. In Togo, OV is multifactorial and contributes to maintaining high maternal mortality by reducing attendance at health facilities [2].

We set up a training program for OV using a participatory technique called forum theater [3], with the nursing staff of maternity hospitals in the Maritime and Plateaux regions. Our study evaluated the potential of forum theater to raise awareness of OV among health care personnel and promote sustainable behavior change. We conducted 15 workshops with 391 professionals (55% of midwives and 25% of birth attendants). Participants completed a questionnaire before and after the intervention, assessing theoretical knowledge about OV and the frequency of violence that could be seen in the services.

Participants reported a 33% increase of OV observed in their daily lives (p<0.05), including twice as physical violence and discrimination. This before-and-after difference was even more pronounced for the midwives, with an 80% increase (p<0.05). All concluded that they would change their behavior towards patients.

Forum theater thus shows promise for improving providers’ ability to recognize and respond to VO. It is an effective tool to improve the attendance figures at health facilities and reduce maternal mortality in Togo.

Keywords: Obstetrical violence; Forum theater; Togo.

Abbreviations: OV: Obstetrical Violence.

Introduction

In 2014, the World Health Organization published a report on the prevention and elimination of disrespect and ill-treatment during childbirth, in healthcare establishments [4]. This publication was based on numerous works carried out internationally, denouncing universal situations of abuse suffered by patients, such as physical or verbal violence, negligence, refusal to relieve suffering, lack of consent to care, lack of respect for modesty and confidentiality, lack of respect and humiliation, discrimination (whether social, ethnic or religious among others), refusal or abandonment of care for financial reasons and detention in structures sanitary facilities after birth in the event of non-payment [1].

Obstetrical violence (OV) is therefore not specific to certain countries or establishments, and several epidemiological surveys find these same behaviors in Togo [5-8]. However, OVs are not only a violation of human rights. They have serious medical consequences, with a recognized link with increased morbidity and mortality of mother and child [2] (Togolese maternal mortality rate of 401 per 100,000 deliveries en 2014 [9]). Indeed, many studies show that the problem of maternal mortality does not lie only in access to hospitals or in the resources of health care structures, but in the violence committed by health professionals, which affects access to health services care, quality and effectiveness [10]. It is estimated that 20% is linked to inhospitality in the causes of reduced attendance of healthcare establishments in Africa, particularly among the most vulnerable populations, such as adolescents, migrant patients, marginalized patients, etc [2-11].

Among the complex mechanisms generating this violence (political, cultural, infrastructural, etc.), nurse training is an essential tool for improving the teams' clinical practices, although it is non-existent during medical and paramedical studies in Togo.

So, the objective was to find a training tool adapted of OV, adjusted to the nursing staff and the spatio-temporal and budgetary constraints of the Togolese health structures. Forum theatre is an interactive theatrical form invented by Augusto Boal in the Brazilian favelas [3]. At first, the professional actors perform a scene relating a conflictual or blocked situation. Then the scene is replayed as many times as necessary, until one of the audience members comes to replace one of the actors (or create a new character) and tries to reach a more satisfactory outcome according to his own scenario.

And so, the scenario allows participants to see themselves act, to become aware of the way in which each participates in blocking the situation, to modify their representation and to consider new ways of interacting. Thus the “re-game” makes it possible to put forward concrete alternatives. The participants react on the behavior of the actors, and not on the relevance of the technical gestures. Several publications in the international literature around training courses using forum theater as a tool to raise awareness of caregiver-patient and OV [12-13,15] concluded that it increased participants' ability to act on their own moral convictions and that it was an effective way to build empathy and improve team communication skills. However due to insufficient staffing levels, they did not obtain significant results in their evaluation.

Thus, OVs are a topical subject, still too little addressed in hospitals. This training intervention through the forum theater was a first experience in Togo, and sought to assess its impact on the behavior of caregivers.

Materials and methods

The training was proposed to all nursing staff in contact with parturients in 19 maternity units in the Plateaux region and 15 in the Maritime region: doctor, nurse, midwife, birth attendants, laboratory technicians, etc. because the whole team can be a source of violence in the exercise of its functions. Participation was on a voluntary basis.

The professional theater company consisted of a host (named the Joker) and two actresses (alternating as a midwife and a patient), who performed four sketches. The scenario of the skits had been written by Togolese and French medical teams, and the director of the company. The first three sketches reflected in a condensed and very explicit way the main VOs; the fourth illustrated the violence exercised by the users of healthcare services on the caregivers themselves.

The setting was simple: a table (which alternately served as a delivery table or as a desk), a loincloth for the parturient and a white coat for the midwife, used by participants when they took her place. The role of the joker was fundamental: he put the participants at ease, encouraged them to participate, ensured that the OV have been recognized and reformulated the interventions of the public aloud.

To evaluate the training, anonymous questionnaires were distributed at the beginning and end of the day. Reading aloud and explanations were given if necessary, to maximize understanding of the items. They were identical except for one final satisfaction item. The questionnaires had to be understandable, relatively quick to complete and their data usable. They included items rating initial knowledge and opinions on the frequency of violence, and their consequences on the attendance of maternity. The participant had to tick boxes according to the answers ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”, or “Every day” to “Never”.

The initial and final questionnaires were compared in order to look for a significant difference between the two. In order to simplify the analysis of the results, the answers "Every day", "Very often" and "Often" were grouped into a category "Often", the items "Rarely" and "Never" into a category "Rarely". Similarly, the items "totally agree" and "tend to agree" were grouped into an "agree" category, and the items "mostly disagree" and "totally disagree into a "disagree" category. The percentages of “Often/Rarely” or “Agree/Disagree” responses before and after the training were compared. For this, a 4-cell Khi2 test was used, when the numbers allowed (greater than or equal to 5), and a Fisher's exact test when the numbers were strictly less than 5, with a confidence level of 95 %, i.e. an alpha equal to 5%.

Each skit and its replays were played successively. The entire procedure usually lasted two hours.

Results

6 training sessions were held in the Maritime region and 9 in the Plateaux region. The health centers having been grouped together to ensure a sufficient number of participants per session, with at least one member of each peripheral center. A total of 391 members of the nursing staff were recorded, which corresponds to around 25 people per workshop.

There was a majority of midwives (55%) and birth attendants (24%) but also administrative staff, laboratory technicians, and more rarely doctors (general practitioners, surgeons or gynecologists) (Figure 1). 80% of the participants were between 30 and 50 years old, 11% under 30 years old and 9% over 50 years old. Only 20 professionals declared having already received training on VOs (3 midwives and 14 birth attendants).

378 initial questionnaires and 379 final questionnaires were held. Although all of the participants spoke, read and wrote French, certain expressions and turns of phrase were not correctly understood, and required a detailed oral explanation.

In all the training, the participation of the spectators was easily obtained. Most of the audience members were quick to express their feelings and take the place of the actors to re-enact the scenes. Improvisation posed no problem, even when the audience was large.

No negative feedback came from the satisfaction questionnaire: 94% of the audience assessed the sketches as relevant and frequently seen in the exercise of their profession. The violence was well identified by the public. At the end of the training, all of the providers concluded that they were going to change their behavior towards patients.

Almost all of the participants left the training with the impression of a good knowledge of OVs, compared to 75% at the start. Before the training, only 45% of birth attendants and 40% of midwives declared that they knew how to define OVs very well.

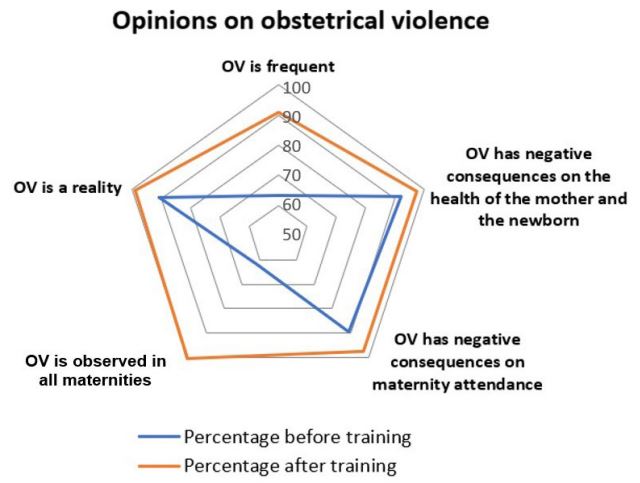

At the end of the training, all of the participants considered that OV were a reality (Figure 2), with a real awareness of the universal and generalized nature of violence. The before-after difference was all the more significant for their frequencies: only 63% of participants found that they were frequent before the training, compared to 91% at the end.

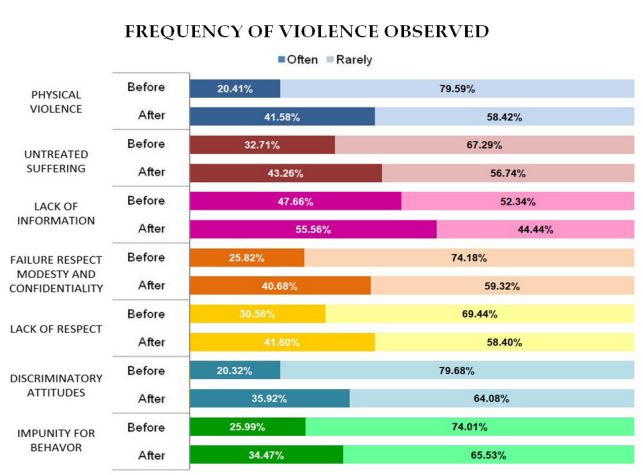

The last part of the questionnaires provided an overview of the frequency of the main types of violence encountered in the performance of their duties. All acts of violence obtained a “Everyday” response percentage at least greater than or equal to 4.4% during the final questionnaire (Table 1). The violence most frequently encountered daily was the absence of identification of the caregiver and the absence of information understandable to the patients.

8.4% of caregivers reported encountering physical violence from caregivers every day, and 43% encountered it frequently. This relatively severe figure was to be moderated with the fact that 11% also declared not to encounter any at all daily.

Table 1: Percentages of “every day” and “never” answers during the final questionnaire, concerning the types of violence encountered in the hospital.

| Types of violence observed | "Every day" answers | "Never"answers |

|---|---|---|

| Physical violence | 8.4% | 11.0% |

|

Abusive gestures (unjustified

episiotomies-cesar- ean sections) |

4.4% | 27.7% |

|

Lack of management of physical or

psychological suffering |

8.8% | 23.3% |

| Lack of consent to care | 9.5% | 19.6% |

| Lack of understandable information for patients | 15.8% | 16.0% |

| Failure to respect modesty and confidentiality | 8.7% | 27.6% |

| No identification | 16.9% | 15.9% |

| Haughty and rude attitude - lack of respect | 9.0% | 23.0% |

| Discriminatory attitudes | 5.7% | 28.9% |

| Access to care prevented for financial reasons | 9.7% | 19.3% |

| Poor quality care | 5.2% | 51.9% |

| Impunity for behavior | 5.0% | 32.1% |

| Refusal of the presence of accompanying persons | 7.8% | 24.3% |

For all forms of violence, an increase in the perception of obstetric violence of +33% on average (average of the percentage increase before-after all items combined) is observed. Figure 3 groups the items for which the before-after difference was statistically significant. Physical violence obtains the greatest increase of 200% in answers “often” between before and after the training. Also, the participants perceive almost twice as many discriminatory attitudes in their daily life after the training.

By comparing the questionnaires of the two extreme ages, the training seemed to have more impact on the younger careers (<30 years old): a three times greater percentage of physical violence observed frequently during the final questionnaire and a doubly increased awareness of the lack of pain management as violence.

In the midwives' questionnaires, there was a statistically significant difference for almost all of the items addressed, except the financial obstacle and the refusal of the companions (Table 2). The percentages of physical violence, abusive gestures, discrimination and lack of quality of care, frequently observed, were about twice as high after the training. Overall, the training led to an 80% increase in the perception of obstetrical violence for midwives.

Table 2: Comparative table of “often” responses concerning violence observed, before and after training among midwives and birth attendants (Coef: Coefficient of comparison before/after with p<0,05, ns: not significant).

| Midwifes | Birth attendants | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violence observed | Before | After | Coef | Before | After | Coef |

| Violence observed | Before | After | Coef | Before | After | Coef |

| Physical violence | 16.8% | 43.8% | 2.6 | 23.7% | 36.7% | 1.6 |

| Abusive gestures | 14.6% | 32.9% | 2.3 | 23.8% | 32.3% | ns |

| No pain management | 32.2% | 46.5% | 1.4 | 26.4% | 36.6% | 1.4 |

| Lack of consent | 36.9% | 52.7% | 1.4 | 26.4% | 38.6% | 1.5 |

| Lack of information | 33.8% | 52.7% | 1.6 | 28.2% | 42.2% | 1.5 |

| Lack of respect for modesty | 25.3% | 46.6% | 1.8 | 23.6% | 34.7% | 1.5 |

| No identification | 44.4% | 56.6% | 1.3 | 30.2% | 36.3% | ns |

| Lack of respect | 27.3% | 45.2% | 1.7 | 27.3% | 36.9% | ns |

| Discrimination | 20.0% | 40.4% | 2.0 | 26.2% | 36.7% | 1.4 |

| Financial obstacle | 41.7% | 50.3% | ns | 33.9% | 38.3% | ns |

| Lack of quality of care | 17.9% | 34.5% | 1.9 | 21.4% | 28.6% | ns |

| Impunity | 28.0% | 46.9% | 1.7 | 26.4% | 35.3% | ns |

| Refusal of accompanying persons |

39.3% | 46.6% | ns | 26.3% | 40.1% | 1.5 |

The last skit concerning the violence suffered by caregivers was the one that made the public react the most. 11.7% of the participants said they suffered from it every day (61.3% suffered from it frequently, by adding the answers “Every day” to “Often”) at the end of the training. This rate rose to 20% among administrative functions (contacts at risk of conflict with the accompanying persons).

Discussion

This work represents the first study in Togo associating forum theater and obstetrics, evaluated quantitatively. It provides data on the reality of OV in these two regions of Togo, through figures from the experience of nursing staff. The majority of caregivers are aware of this reality and its consequences on hospital attendance, and obstetrical violence is present for them on a daily basis. Half of the caregivers declare that physical violence is frequent in their practice but almost half also denounce impunity for behavior. Depending on the work environment (urban or rural, university or not, etc.), it's clear that there can be considerable variations in behavior, even if the analysis could not go into this level of detail.

The forum theatre has once again proven itself in terms of prevention, management of conflict situations and behavioral anomalies, and made it possible to approach OVs with tact, by thwarting, through a climate of benevolence and interactivity, the guilt and shame that can restrict dialogue with healthcare teams. The re-games always highlighted the importance of the relational (in particular communication, explanation, consent) and the structural (display of prices, dedicated examination room). The solutions concerning the non-drug management of pain that emerged were related to humanized childbirth methods (breathing, mobilization, but also psychological support, empathy, gentleness). Several experiences, notably in Tanzania and Senegal, confirm that humanized childbirth methods have a positive impact on teams, offering them a new field of action that can be achieved with limited financial resources and without taking up their care time [17].

However, this evaluation experimental necessarily implied biases in the questionnaires: comprehension problems, poor reading and writing skills of a certain number of participants, proposals too insinuative or not detailed enough, with risks of confusion in the analysis. However, on the before-after analyses, the majority showed a significant difference, which supports the consistency of the questionnaires. This work has revealed the difficulty of quantifying such a subjective qualitative notion that is OV, and of evaluating an impact afterwards.

The results confirm a positive impact of forum theater on the perception of OV in the short term. However, a long-term quantitative study, questioning the patients, would be necessary to reinforce these results. Similarly, the increase in the rate of attendance at maternity wards would in itself be an objective indicator of the changes induced. The positive results of this study therefore invite us to perpetuate this experience in continuing education throughout the territory through local trainers, thanks to the availability of the scenarios of the sketches and the films made during the training sessions, in order to that other theatrical teams appropriate the principle.

Finally, to have a real impact, training must also be accompanied by concrete political, budgetary and societal actions (recruitment of staff, appropriate equipment, laws and sanctions, combating violence against women, etc.). And it is logical to think that these measures will mechanically contribute to reducing violence against nursing staff too.

Conclusions

These results confirm that OVs are a sensitive reality and a key issue in Togo. An intervention using improvisation and participatory theater techniques is an effective way to discuss the behaviors, causes and individual solutions to be provided to reduce abuse and lack of respect for patients to the hospital. Its interactive form allows the support of all the staff and ensures that all the participants leave with a concrete knowledge of what the used vehicles are.

The analysis shows an overall increase of 33% in the perception of OV on a daily basis, in particular twice as much physical violence observed frequently and twice as much discrimination. This difference was particularly marked among midwives, and confirms that this is a target audience for this training.

However, this awareness will only have weight if it continues through continuous training within the teams. This is possible by the fact that it is easy to set up and does not require a budget or expensive equipment. This structure of forum theater can be transposed to other countries, since the OVs are a universal fact. It encourages the development of new strategies to increase the rate of attendance at health facilities and thus prevent maternal mortality on a global scale.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding sources: Our training on obstetrical violence is part of the MUSKOKA program funded by the Agence Française au Développement, and managed jointly by the non-governmental organizations Gynecologie sans Frontières, Plan International and Handicap International, under the control of the Ministry of Togolese Health. This project, aimed primarily at reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, included a first phase of renovation and re-equipment of maternity wards in the Maritime and Plateaux regions. The second phase was that of the training of nursing staff, with programs relating to obstetrical ultrasound, the use of the cardiotocograph, obstetrical analgesia and obstetrical violence.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank the entire Nyagbé troupe and its director Olivier Dubois for their participation in the project, which determined its success. We also thank the members of the Ministry of Health and all the midwives and doctors who accompanied us during the training. Finally, we also thank the French Development Agency for the practical organization of the training sessions.

References

- Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring Evidence for Disrespect and Abuse in Facility-Based Childbirth. Plos One 2015.

- Warren C, Abuya T, Obare F, Sunday J, Njue R, Askew I, Bellows B. Evaluation of the impact of the voucher and accreditation approach on improving reproductive health behaviors and status in Kenya. BMC Public Health 2011.

- Boal A. The Rainbow of Desire: The Boal Method of Theatre and Therapy. 1st Ed. Routledge. 1995.

- The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth: WHO statement. World Health Organization. 2014.

- Liens entre violences faites aux femmes et mortalite maternelle: Cas de 7 pays en Afrique Subsaharienne et en Haiti. ONU Femmes 2015.

- Audit des pratiques socioculturelles en matière de santé maternelle et néonatale au Togo. ONU Femmes/ GF2D. 2014.

- Bassowa B. Evaluation de la qualité des soins obstétricaux à la maternité du CHU-Tokoin de Lomé. Medical thesis. 2006.

- Douti P. Si tu ne pousses pas, tu vas tuer ton enfant ! Sagesfemmes et mères face aux morts périnatales au Togo. Santé Publique. 2020.

- Rapport d’activités 2016. Les Nations Unies au Togo. 2016.

- d’Oliveira AFPL, Diniz SG, Schraiber LB. Violence against women in health-care institutions: an emerging problem. The Lancet. 2002.

- Kruk ME, Paczkowski M, Mbaruku G, de Pinho H, Galea S. Women’s Preferences for Place of Delivery in Rural Tanzania: A Population-Based Discrete Choice Experiment. Am. J. Public Health 2009.

- Brüggemann AJ, Persson A. Using Forum Play to Prevent Abuse in Health Care Organizations: A Qualitative Study Exploring Potentials and Limitations for Learning . Educ. Health. 2016.

- Swahnberg K, Wijma B. Staff’s perception of abuse in healthcare: a Swedish qualitative study . BMJ Open. 2012.

- Zbikowski A, Brüggemann AJ, Wijma B, Swahnberg K. Counteracting Abuse in Health Care: Evaluating a One-Year Drama Intervention with Staff in Sweden. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2020.

- Infanti JJ, Zbikowski A, Wijewardene K, Swahnberg K. Feasibility of Participatory Theater Workshops to Increase Staff Awareness of and Readiness to Respond to Abuse in Health Care: A Qualitative Study of a Pilot Intervention Using Forum Play among Sri Lankan Health Care Providers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020.

- Nyagbé : Du théâtre dans les milieux scolaires pour le développement personnel de l’élève. www.togocultures.com

- Horiuchi S, Shimpuku Y, Iida M, Nagamatsu Y, Eto H, Leshabari S. Humanized childbirth awareness-raising program among Tanzanian midwives and nurses: A mixed-methods study. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2016.